Woodland Heritage Survey

Share this page

It was probably not the day many of us had imagined when we signed up for the Celebrating Woodland Heritage survey at Hardcastle Crags, a small hardy group of us gathering in the car park amid light but persistent rain. Snow had been forecast but only touched the higher ground, and down here the slushy wetness lent the woods a sombre air. Alfie looked miserable and stood shivering while gazing wistfully at distant squirrels.

‘Believe it or not, this is the best time to survey’, explained Chris Atkinson, the project officer at Pennine Prospects. ‘You can see so much further when there are no leaves on the trees and there is little ground vegetation to obscure what we’re looking for.’

What we were to be looking for was historical features, the sort hidden beneath the woodland canopy and often deep beneath mud, leaves and bracken, the sort that lay unmapped and undiscovered potentially for many centuries. For this we would need a camera, a tape measure, a GPS, a compass, a notebook and a red and white javelin (used to give an idea of scale in all photographs). One of our party, Diana, was equipped for far more; with a foldable stool, first aid kit, emergency blanket, tea and biscuits, we could probably survive being snowed in for a week. Before Chris had finished the talk-through, the paper in his pad had turned to mush and the camera lens was steamed up. He turned to the all-weather notepad and we all hastened to move before our fingers were rendered useless for writing. In fact, mine already were past that point and so I ended up being in charge of the camera. My key instruction; don’t lose the lens cap. With this in mind, I took the cap straight off and placed it carefully in the bottom of the case for the rest of the day.

For a while, exploring the area above the car park, there seemed to be an awful lot of walls. But it turns out dry stone walls are very interesting, with Hywel particularly enthusiastic about the differences between the regular and irregular walls we now tend to build and classic single (just lines of single stones) and othostatic (built around and incorporating large natural boulders) walls. In these walls we discovered old gateways with stang posts, stoops that have holes for wooden bars to be inserted. Soon after, we explored the site of Winter Well, a dwelling inhabited until the mid-19th century but with only its pantry room remaining with stone alcoves built into the hillside. Still, there were a lot of cooks; six of us recording a single feature and only poor Dave with his notepad and frozen fingers doing much work. So we split into two and spread out to explore the open woodland beyond.

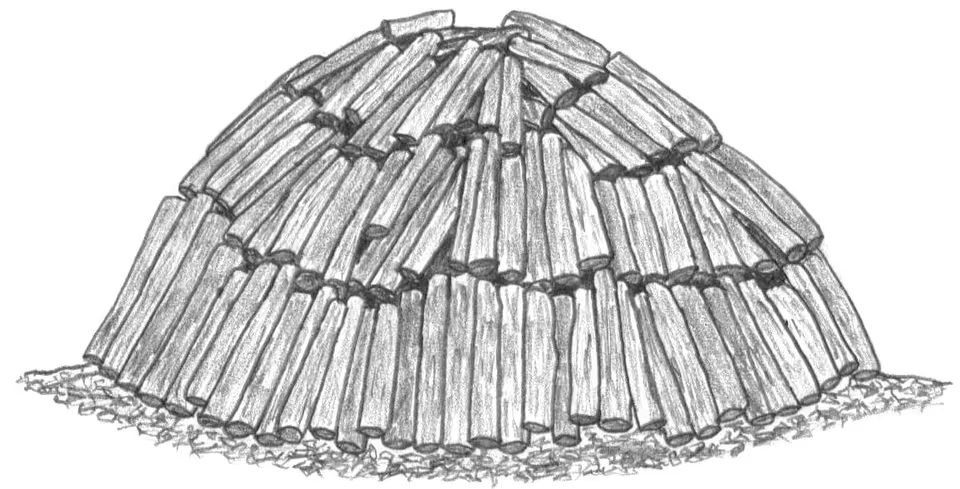

This is what we had come for, to wander the apparently empty and unmapped expanses of woodland to find subtle historical clues along the leaf litter. To my surprise, there is no science to this, just an aimless zigzagging meander across a given tract of woodland, not entirely dissimilar to the way I research my books. But three pairs of eyes looking explicitly for historical features yields a surprising amount. We had not gone 100m when I picked up a flattened area some distance below. Sure enough, it was an unmistakeable charcoal platform dug into the hillside. What surprised me was that it was just 5m from a path that one of my woodland routes followed and I had never seen this feature. It was built up with a crude wall from below that partly utilised a huge natural boulder, but in summer it would have been covered with bracken, almost invisible.

Rejuvenated by this find, I gambolled up the slope again, a muddy scree that slid away beneath every step. My eye in, I picked out another platform from below, though this turned out to be cut through by the old stone-surfaced packhorse route of Willow Gate. I thought I must be wrong, but Hywel found charcoal in the bank below and excitedly explained how old this hearth must be. It must have predated the surface of the track and thus was likely to be at least 400 years old, if not more. It had stopped raining I think, but these finds were enough to help us forget entirely about the weather. I soon found the faint tracing of an old single wall, then Diana was shown to another charcoal platform by a dog walker who had wondered what this feature was. This one, beneath pines, was unmistakeable and we gathered for lunch on its flat surface. Diana perched proudly on her stool and we sat on the ground chattering about our finds until the rain returned abruptly and sent us back on our quest.

It is a time-consuming process, this scouring of the heaves and hos of the tumultuous woodland earth. Occasionally someone would yell and our sub-team would gather to assess the merits of a particular lump or heap of rocks before beginning the detailed recording of each feature. Having picked up five charcoal platforms, half a dozen walls and some intriguing pits and holloways, we were surprised when Chris informed us that it was nearly 3 o’clock and time to knock off for the day. Time had flown and I slightly regretted having commitments for the following day for I longed to continue the search with our team that was just beginning to find its surveying wings.

Back at the cars, we gathered the kit and, as I handed over the camera, I proudly proclaimed ‘At least I’ve not lost the lens cap’. I didn’t think I needed to check, but someone else did and it was not there. Somewhere along the way the open bag must have been tipped over as I scrambled up and down muddy slopes. I skulked shamefacedly away and, although I may not be allowed back, anyone interested in volunteering for these surveys (of which there are plenty more over the coming months) should contact Chris Atkinson at Pennine Prospects Chris.Atkinson@pennineprospects.co.uk or visit www.celebrate-our-woodland.co.uk - who knows you may even see the woods on a brighter day.