The Rhiangoll Valley

Share this page

There is an intriguing and beautiful valley between the western flanks of the Black Mountains and their offspring outliers, Mynydd Troed and Mynydd Llangorse. From above, it is a gentle green valley of woods and scattered farm buildings far below the great broad shoulders that the table topped peaks of the Black Mountains thrust out into it. The bracken-covered hillsides are generously spun with lovely grassy tracks and deep lonnins covered over by trees, some almost entirely blocking out the daylight. Occasionally they emerge from the trees to reveal deserted farmhouses or plush cottages. At the bottom end of the valley is the village of Cwm Du, its tiny lanes and church marred by the A479. It houses a great local, the Farmers Arms, at which I’d sampled local beers and listened in to chatter about ram sales from some Cornish visitors, who tucked into massive Welsh steaks and talked prices, breeds and stock with a remarkable amount of laughter. The landlord then treated us to the tale of the local boy who used to steal knickers from houses and washing lines. “He was caught one day jumping over someone’s back wall with a handful of knickers.”

At Sorgwm, high up on the edge of the mountain, there is a couple of buildings marooned amid the bare sweep of bracken and thorn trees where I meet the resident farmer. He is an elderly man, with small blue eyes, active folds in his face and wisps of long grey hair flailing from his ratty cap. Though busy – while working I have seen him dashing on his quad to fell a couple of branches then dig some holes in the bog for the sheep to drink from – he has time to talk and talk. He asks me where I’m from and eventually what I am doing, taking me for a tourist initially.

“Well it’s all dropping off now anyway. You’re the only walker I’ve seen today and it’s been a quiet old summer. Back in the seventies, the hills were covered in them, but not anymore. They’re bringing in this Tir Gofal, but it’s too late for that now. Pretty soon you won’t be able to get up here anyway,” he exclaims, gesturing up the hillside behind him. “All these schemes they’ve got, they won’t mean anything you know if there are no farmers there. Him down there, I found him dead under a tractor in 1990. It’s derelict now, everything’s been abandoned.”

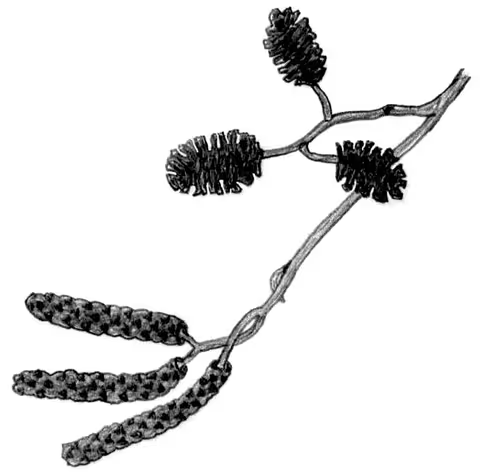

We both look down towards the next farm on the hillside in momentary silence, but before I can say anything he continues in his mild Welsh lilt. “We’re down to two of us left in the valley and no-one’s laying any hedges. We did one last year but we weren’t paid for it. And I’ve only had fifty lambs this year… Too many of them covered in ticks too because I haven’t been able to burn for the last two years. Look up there where you see those thorn trees, that’s not been burned and the sheep can’t get at them, so the trees are coming up. They’re everywhere now, so high, and soon there’ll be nothing but thorn trees and nobody’ll be getting there then. You try and tell some of these people from the National Park that you know a thing or two about this, but they won’t listen. Do you know what? They’re destroying the countryside, that’s what they’re doing with all their schemes.”

He is wearing a dirty white shirt and a barely intact, largely unwound red and white cardigan beneath a grey suit jacket, with a pair of waterproof trousers and wellies. I imagine him walking into the Farmers’ Arms in exactly the same garb. “You can never tell what it’s going to do now. It used to be if you had a bad week, you’d always get a couple of good ones after that. But now it’s all extremes. You know we get a cloudburst here in this valley, it comes once every twenty-five years and the water runs down the sides of the valley waist-deep. It happened last year and I got taken by it. I saw the water coming but there was nowhere I could go. There were cows paddling around in it. It took the bridge out down the bottom and carried whole hedges from here to there. We had one in 1956, one in 1977, but my dad said he never saw anything like that before.”

He shakes his head, the way farmers do, before adding, “We live in a changing world, that’s for sure.”