The Hunt for Shirl Fork

Share this page

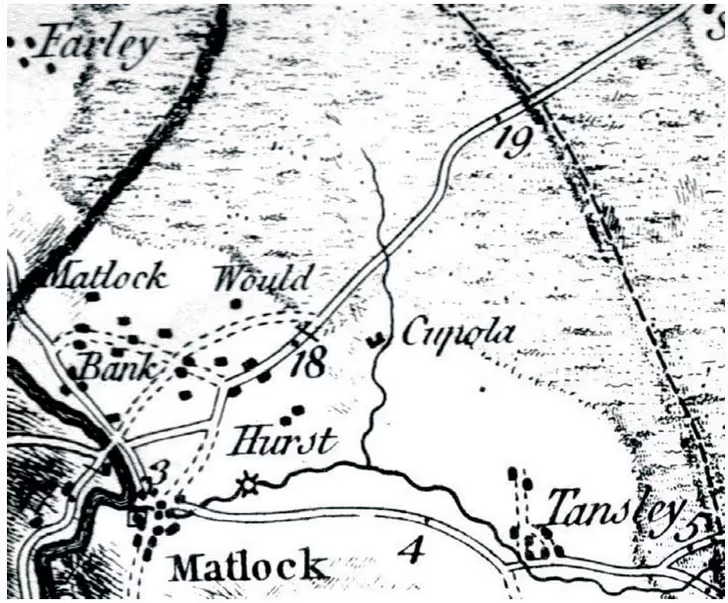

In the course of writing my books, there are places I end up going back to repeatedly, normally because I have missed something first, second and third time. Chatsworth Moors, the furthest straggle of the gritstone peat moors of the Pennines down towards Matlock, hold their secrets close. While the moor directly above Chatsworth is reasonably accessible, those parcels to the south of Beeley Triangle are very difficult to access in the first place. You end up jumping over locked gates or searching the long enclosure-era walls for any way through. The OS map shows little of interest here; a few old quarries, the intriguing name Raven Tor and a line of diamond-shaped enclosures on Harewood Moor.

I have already trudged through the thick heather here twice when I read about Shirl Fork, which research informs me was first referred to in the 13th century and may once have marked the line of an ancient route called Herward Street. It may even have marked the boundary of Mercia and Nurthumberland in the Dark Ages. Its name possibly comes from the same root as Carl Wark, an Old German word that became churl and was bastardised to Charles Fork in some records. George Wigglesworth has suggested it may relate to sirle, an Old English word for armour that died out in the 14th century, and the fork refer to a long-lost gallows at this important site.

So, armed with a clear grid reference, I go in search of this ancient boundary marker, skirting along the edge of Harewood Moor until I get to the spot where I am supposed to be able to look over the modern boundary of the moor and see it. Only I can’t see anything in the huge tilled pasture that is part of Moor Hall Farm, but there is a stoop built into the boundary wall. It looks like any gritstone stoop, but could this be the ancient stone. I follow the wall further to make sure I haven’t stopped too soon and find several further fine stoops built into the 19th century enclosure walls, most as gate stoops for gaps that have since been blocked up. I realise quite how many stones there are within a few hundred metres of the grid reference I have been given. In theory it could be any of them, but how would one know?

Back on the nearby road, I head to the junction of four roads, where a guide stoop stands on the corner opposite Screetham House Farm. It too is built into a wall as a gate stoop, but its age is obvious from the places and arrows etched into its faces. It was one of many guide stoops erected across Derbyshire in the mid-18th century, when Parliamentary decree required all moorland routes be marked at every junction. There were no walls here then, just open moorland, something that is particularly hard to imagine in this corner of the moors, where roads have sliced the once-open country into dozens of awkward pockets. I trudge back along the busy road in the rain; these lanes are all well-used rat runs on whose straight lines cars cavort at great speed. I give up on this quest a day, settling for an equally fruitless search for an abandoned trough near Raven Tor.

After a discussion the following day, though, I come back for more. The grid reference it seems was wrong and the stone I am told is some 700m away to the west. In fact, it is visible from the road I had trudged along the previous evening. Shirl Fork stands innocuously in a field at the edge of Harewood Moor, but is a fine carved stone that is marked with a number of crosses. It stands now at the junction of Beeley, Harewood, Darley and Ashover parishes and lines up with a number of other interesting local features. On Beeley Triangle there is a cross base lost in the heather, and another can be found beneath Harland Edge, all three within a mile of each other. The landscape keeps giving, reluctantly perhaps, but bit by bit once can start to piece together its history and the changes it has undergone.