The Rough Bounds of Knoydart Part II

Share this page

The Sunday is the day we’ve all been waiting for – a clear sunny day in the Highlands – and I awaken early at the prospect. Before breakfast I take a walk along the loch shore until I reach the sun. I sit on the rocks and gaze into clear waters where there had only been a muddy estuary yesterday and am tempted to swim until I try the water temperature. Ladhar Bheinn and Beinn Sgritheall stand as imposing sentinels either side of the loch and I gaze up at all the rocky features I had been unable to take in on yesterday’s walk.

By the time I return, half of the campers are already heading out into the hills, but we strike camp lazily as our planned walk is barely 5 miles today. Sun beats down as we head up the side of Gleann Unndalain and we cake ourselves in cream and drink greedily from the stream in preparation for a hot day. We soon reach Mam Unndalain and leave the path for the rugged slopes of Luinne Beinn. There is no real path and we weave through slabs and crags below the complicated ridgeline. Climbing such rough ground with heavy bags is hard work in the heat, but there are spectacular views down over the River Carnach to the wild slopes of Beinn an Aodhainn and Sgurr na Ciche, where rock seems to cover inch of the ground. This is the vision I’d had of Knoydart, of a truly rugged and untamed landscape into which people quickly disappeared.

The wind fills in from the east as we climb and cloud rolls in with it, our sunny day evaporating in an instant. After a brief detour to the summit of Luinne Beinn, we shelter in a perfectly placed crevice where we had stowed our bags just as rain drove in. Lodged between these rocks and with an updated weather forecast on our phones for the first time, we realise we are not in for the beautiful evening we had envisaged when planning to wild camp by one of the lochans high on the ridge between Luinne Beinn and Meall Bhuidhe. Instead strong wind and rain were due to reach us by the early hours, so we decide we still have time to continue over Meall Bhuidhe and descend all the way back to Inverie in time for a couple of pints in the pub.

The ridge between these two remote Munros is rugged but the going is helped by an insistent path that winds its way through the crags and slabs. It is surprisingly busy though and we meet more people here than anywhere else on Knoydart except at the bothy. It turns out we are not the only ones wanting a taste of the wilderness on this fine day, and we tell many of them we will see them in the pub later. The sun returns as we scramble up the jagged schist onto Meall Buidhe, its mirror-like flecks of quartz glinting brightly. It is as though someone has scattered glitter all over the mountain, just as it had seemed when my boots and trousers sparkled after yesterday’s walk. When the sun is out, it’s hard not to see magic all around you on Knoydart.

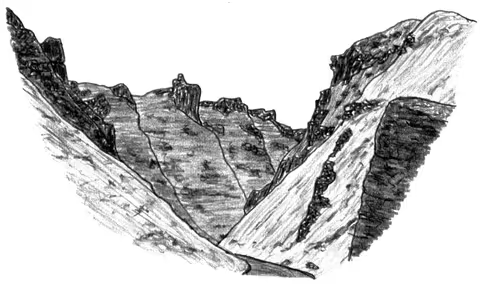

It is a wonderful descent from Meall Buidhe along the grassy ridge heading south-west straight towards Inverie – though 6 miles away, it feels like we’re almost back. The ridge has a sting in the tail though, its last 250m dropping steeply through the rocky crags of Druim Righeanaich to the valley below, one last technical challenge before the track leads back into the village. Dave is particularly knackered and we finish the last of the water before starting the descent. After the first few yards as I am eyeing up an awkward rock gully, there is a loud cry from behind. I race back up to find Dave on the ground, clutching his ankle. ‘I heard it crack,’ he exclaims, saying he feels sick. He slipped and his tired leg twisted under him, pushed down heavily by the weight of the pack on his back.

So close and yet suddenly so far away. Even the track seems a long way off and it is already nearly 6pm. After a bit of discussion and a realisation that the closest Mountain Rescue post is probably in Kintail, Dave tries to put weight on his right foot, which he manages to do with the aid of his walking poles and through an immense amount of pain. He says he’ll try and get off the ridge and, once down on the track, I can go to get some vehicular help to get him back to Inverie. But the descent is far from straightforward as he lowers himself down rock steps and gullies and across precarious boggy shelves. It feels there is little I can do but to offer him encouragement as there is no way to carry two large packs. Dave grimaces as he inches his way down and, after 75 painful minutes, we reach the foot of the last crag. An unpleasant-looking bog stretches away towards the main river, but away to the left are some trees along the Allt Gleann Meadail stream and what looks like a barn just beyond. We have given up on there being anybody there, certainly any potential transport, so Dave insists he wants to head for the track instead of pitching a tent for the night. It starts to rain as he moves off across the bog, while I head for the burn to refill our bottles.

As I’m bending down by the stream, I notice someone in the window of the building opposite, which is not the ruin it is marked as on the OS map. I quickly remove my boots, roll up my trousers and cross the burn, before scrambling up the muddy bank to the door. I must look a bit of a state as I appear barefooted before the bearded occupant. I explain what has happened, but he like us has no mobile service and no transport other than the bike he rode in on. He explains in a gentle Scottish brogue that it is a private bothy they have rented, but that we can stay the night if that helps as there are only three of them in the whole place. Thanking him, I race back through the river and across the bog. I see Dave hunched over in the middle of this wasteland, moving awkwardly as rain drives in, and shout for him to stop. We have an out – we are both hungry and tired, and can at least postpone the problem of getting to the village until the morning.

Collapsing into the bothy, Dave removes his boot to reveal a massively swollen ankle that we are still assuming is just badly sprained. Paul lights a fire and offers painkillers, while I cook up tea and pasta. We are offered wine as it is their last night and there is still a whole bag full left, and we feel very fortunate as rain and wind buffet the glass of this beautifully-renovated bothy. The other occupants soon return from the pub in Inverie after a long day on Ladhar Bheinn, and one of them promptly vomits repeatedly outside the door (we will forget this while heading out barefoot in the night for the loo!). Paul would have joined them, but he had injured himself while cycling back from a distant restaurant at the far end of this ever-surprising peninsula. Plummeting down the hill on the only road, he was going at 30mph with no lights and no helmet when he rode headlong into a deer and flew off the bike and over the top of it onto the road beyond. After a few moments, both Paul and the deer had picked themselves up and headed off in their different directions. It turns out all three of them are doctors, so one offers some advice on what Dave should do, most notably that he should still get checked out at the hospital in Fort William.

After the wine and some of the whisky we are still inexplicably carrying back out of Knoydart, I hoped to sleep better on the wooden mezzanine platform. But I’m still on a thin Thermarest mat and Kenny makes a lot of noise on his massive airbed, so I lie awake as wind whistles through the rafters and am grateful we are not camping at 2,000ft. In the morning, Dave says he thinks the swelling has dissipated a little and we give ourselves nearly 2 hours to walk the 2½ miles to the ferry in Inverie. He moves reasonably well, though still mostly supported by his walking poles as he drags his leg along. Halfway back we manage to cadge a lift in a truck with some guys working on a hydro-electric scheme in the valley, so we find ourselves in another massed throng waiting to return to the mainland, with several familiar faces now among our fellow travellers. Back on the boat, Knoydart disappears behind into the mist from which it had emerged four days earlier, having very much left its mark upon us.

Post-script: When Dave was checked out at Belford Hospital in Fort William, it turned out not to be just an ankle sprain – he had broken his fibula in two places near the ankle. He emerged a couple of hours later in a moonboot, which he would have to wear for 6 weeks and not drive for 8 weeks. I regretted telling stories of my own ankle sprain mishaps fell running and the painful walks out, when Dave had somehow dragged his shattered ankle down some of the hardest terrain possible. In retrospect we probably should have called Mountain Rescue straight away, but having been on a team for several years himself, Dave had not wanted to be one of those idiots hauled off by helicopter after rolling their ankle. Either way it would have taken me at least an hour to reach somewhere I could have phoned from and a long wait for Dave in the rain as darkness fell. These decisions are rarely simple.