In Search of Houndkirk

Share this page

Houndkirk Road is a fantastically named ancient highway across Burbage Moor between Ringinglow and Longshaw, but seems something of a barren trudge across a lonely shoulder of moor. My school used to use it for its cross country races, bussing the whole year to the far end of the track and then letting us race back to Whirlow via Limb Valley in the wind and rain. It always seemed like a godforsaken place and doubtless remains a place of torment for those who didn't relish cross country as I did.

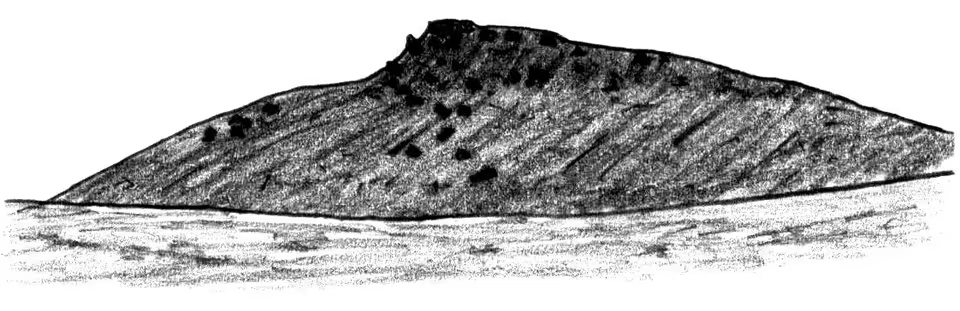

Returning to map this part of Burbage Moor for my South Yorkshire Moors book, I found it still surprisingly empty, particularly when compared to the dense maze of paths, boulders, quarries, cairns and tors on the other side of Burbage Edge. Though Houndkirk Hill and Houndkirk Edge are a pleasant detour, there is little opportunity to get off Houndkirk Road, the broad sandy motorway that cleaves the moor in two. Even the true highpoint of Burbage Moor is lost in the deep heather far from any path. Marked only by a sad little cairn, it is shown on old maps as Mudge's Station, referring to William Mudge, an 18th century director of the Ordnance Survey. There are relatively few of these in the country and they are usually primary sighting points like Ingleborough and Salisbury Plain, but here at Burbage the fact that this is even a natural top at all is largely forgotten.

So it was with some surprise that I found myself chatting to Richard Carr about various features on Houndkirk Moor that I had never heard of; Houndkirk Angel, Ponslow Cross, the Starfish site and Burbage rock cannon. As a result I arranged to meet up with Richard to explore the area. Within moments of setting off up the road, he was pointing out the outline of a building that had been used as a guard house during the war. Just over the brow, laid out across a large swathe of moor was a Starfish decoy site, one of several built to simulate the streets and steelworks of Sheffield at night. There was a bunker on top of the hill (which was used later on in the war for an experimental Radar station), where soldiers sheltered while hoping the Germans would drop bombs on them and not the city. It worked too, as various bomb craters are scattered across the moor, now largely concealed by the heather.

A few yards away, on a flat boulder on the top of this shallow but very prominent brow overlooking most of the city, Richard pointed out the remains of Ponslow Cross. The shaft had broken into four parts, with one erected in the original socket in the rock and the others lying scattered around. Richard was adamant the wrong section had been set in the socket as another was larger and appeared to fit better. The cross was evidently a large landmark at the crest of this ancient highway, but now it is hard to find any reference to this lost guidestone.

Another 100m along the road, past the decoy site and the outline of a field where the Duke of Rutland tried unsuccessfully to grow oats to feed his grouse, we ventured off into the heather again. Beneath a natural rock shelter was carved the Houndkirk Angel, a unique and beautiful butterfly-like design that Richard thinks may have been carved by an 18th century quarryman. "Imagine him sitting under here in the rain and playing around with a design in the rock. You can see that it is pecked not chiselled, so its probably pre-19th century."

Over the hill, we dropped down to Burbage Edge (though there is some debate about this name - on old maps it is marked in different parts as Wild Moor Stones Edge and Reeve's Edge) ad Richard spoke about the army training range that covered this valley during World War II. "I think it may have been used in the build up to D-Day. They approached from the valley as if crawling up the beach towards the cliffs of Normandy and all the shot marks are in the same direction." I wandered up to some rocks on the brow that were peppered with pock marks from all manner of weaponry. It is the same with the popular climbing boulders below, which are only climbable due to the holds created by these shot marks.

One of the many rocks beneath Burbage Edge that is riddled with holes looks slightly different from the others. It'd be easy for the layman to assume it was different sorts of bullets, but Richard is not a layman. He started out working in his family's stonemasons and is full of information about the sort of drilling, chiselling, and plugging used in various different forms of quarry work through the ages. What we were looking at was a rock covered in drill holes not for the purpose of extracting stone, but rather for playing tunes on. The holes were dug to different depths and small charges placed in them with different lengths of fuse so that a tune or royal salute was played when they went off. This is what Richard had referred to as a rock cannon. "I don't know of any others in Derbyshire. There's a lot of them in the quarries of North Wales, so perhaps some Welsh quarrymen were working here and brought the idea across with them."

You don't have to look very hard to find millstones scattered around Burbage Quarries, some completed but unsold, others crude shapes that were barely started. What I hadn't apprciated was the difference between the early millstones with rounded mushroom faces and the later flat stones, or even between crushing stones and millstones. Crushing stones are larger hunks of rock used for pulping wood or creating paint, and are often identifiable by having square rather than round holes at their centre. How these several-tonne bohemoths were removed from the site is hard to fathom given they are usually hewn in the middle of a boulder field.

Returning to the car, we passed a mammoth stone trough, which had been abandoned on the edge as it had cracked when the quarrymen worked on it. Further on, there was the site of a shelter built into the side of a boulder. The footings of the walls were clear, as well as grooves for gathering water running down the rock and a stone where the blacksmith's anvil would have struck. There are many similar sites dotted around these quarries; blacksmiths were very important to keep all of the quarrymen's tool continually sharp. There was doubtless more too that remains hidden, lumps in the ground that remain unexplained. All of this history crammed in a 2.5 mile walk just off the bottom end of the Houndkirk Road. Now if only Richard was able to accompany me on all my walks and explain the nuances of the landscape I have missed.