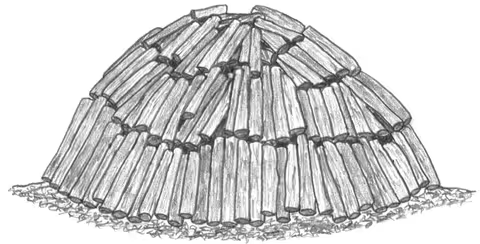

Well, thanks to the good folk at Woodlands.co.uk I have recently been the proud recipient of a 2017 Woodlands Award for one of the Best Woodlands Books of the Year for The West Yorkshire Woods: Part 1. It is particularly satisfying as this is a respected woodland management organisation and my layman's guide to woodland history and exploration in the Calder Valley has obviously met with their approval.

The Kentish Coast (or should that by the Old Coast of Kent) is a surprisingly varied affair, combining dizzying chalk cliffs with golden sands and endless shingle beaches. I began at Broadstairs in the middle of Folk Week, but before nine in the morning there was little sign of it on the streets. The tidy arc of Viking Bay is a colourful pageant to the classic English seaside, with an old Punch and Judy stand as its centrepiece. I set off below the low dirty white cliffs – this part of the coast path is not yet open, but it is easy to trace a route round to Ramsgate along the cliffs. The town is reached by a set of stone stairs built into a fake section of cliff, exposed by the fact it is the colour of gritstone and not chalk. The chalk cliffs of the North Foreland continue until Pegwell Bay, where a Viking ship celebrates the first Saxon invasion here in 449. The crazy Danes who built the replica sailed it across the North Sea in 1949.

Kinder Scout held a particular thrall over me when I was younger, the highest point in the nearby Peak District but respected to the point of reverence. Its featureless plateau was something to be wary of. I only remember crossing it once, when I was considered old enough for this undertaking and I emerged on the far edge some distance from where I was intending. Maybe because instead of using a compass, I tried to navigate the maze of deep groughs leading into the hinterland from Kinder Gates. When finally this ran out and I neared the watershed, on which the theoretical (but invisible) high point was located, I climbed out of the grough into a remarkable landscape. I stood above a warren of black channels that stretched as far as I could see in every direction, bare peat onto which clung a thin covering of grass on the higher islands. The vision stayed with me, as of a desert, a peculiarly soggy but equally bewildering one.

There is an intriguing and beautiful valley between the western flanks of the Black Mountains and their offspring outliers, Mynydd Troed and Mynydd Llangorse. From above, it is a gentle green valley of woods and scattered farm buildings far below the great broad shoulders that the table topped peaks of the Black Mountains thrust out into it. The bracken-covered hillsides are generously spun with lovely grassy tracks and deep lonnins covered over by trees, some almost entirely blocking out the daylight. Occasionally they emerge from the trees to reveal deserted farmhouses or plush cottages. At the bottom end of the valley is the

A number of times over the past dozen years I have been summoned to mid-Wales to undertake a rather unusual Rights of Way survey. It is the same as many others I have done except the paths just aren’t there, so it feels like walking a series of notional lines on a map which may as well have been made up (which in many cases they were, as plenty of Welsh landowners have been keen to tell me). However, every so often – in between vaulting perilous fences, pushing through thorny hedgerows and squelching through knee-deep muddy fields – surprising features are revealed in a landscape that, when I do manage to take the time to look around me, is as beautiful as anywhere I can imagine. There are none of the bare rocks of Snowdonia, but Powys is just as dramatic in its way, a constant procession of smooth hills and deep valleys bounding as far as the eye can see.

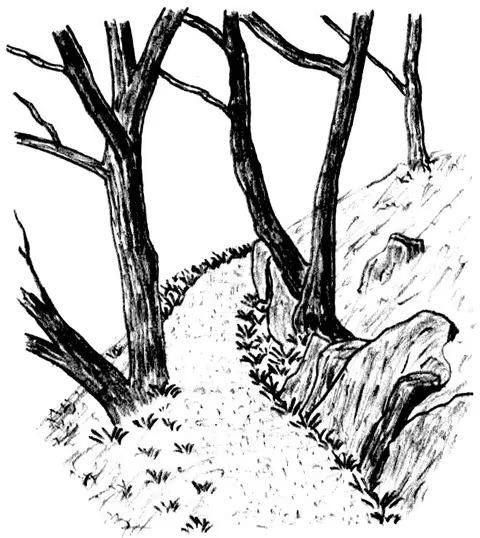

It was probably not the day many of us had imagined when we signed up for the Celebrating Woodland Heritage survey at Hardcastle Crags, a small hardy group of us gathering in the car park amid light but persistent rain. Snow had been forecast but only touched the higher ground, and down here the slushy wetness lent the woods a sombre air. Alfie looked miserable and stood shivering while gazing wistfully at distant squirrels.