About Christopher Goddard

I was born in Sheffield in 1978 and grew up in Oughtibridge on the north-west side of the city. The Bradfield moors on the edge of the Peak District were just a short walk away, while our house led straight out into the woods of the Upper Don Valley. I have been drawing maps as long as a I can remember. Wharncliffe and Beeley Woods were mapped and remapped many times over the years, with more detail being added as I honed my youthful craft. My brother and I gave names to every lost quarry and mine-working, like the great basin of Ngorongoro in the middle of Great Hollins Wood, inspired by a David Attenborough wildlife programme. On holidays in Greece, I was appalled at the standard of the maps and worked to create a decent plan of Kassiopi and its surrounding coastline. Some of these I still treasure, others are sadly lost.

Finding a new path or interesting feature and committing it to the map was what drove me on in these endeavours. My mother said I was born a good century too late and should have been out exploring and mapping the world in the age of empire. Yet the exploring I like to do need not be particularly exotic, rather it just has to be somewhere new – and you can discover new things around the corner from your house every day. Exploring is also not linear, but nearly always leads me round in circles as I am desperate not to miss anything. Indeed this is the only way to make a good map.

After leaving Sheffield for university, I stopped making maps for a number of years, other than a few sketches in my journals or notebooks. Instead I was using maps in my work – highly-detailed GIS maps that were very different to what I had grown up with. I became a Rights of Way and National Trails surveyor, first at the Lake District National Park and later as a freelance contractor, working all over the country. I was delighted to be paid to explore places like Cornwall, mid-Wales, the Gower, Berkshire, Cheshire, and the Cambrian Mountains, but there was no need for me to draw maps. Everything I needed was provided, and instead it was left for me to find mapped routes on the ground.

When I moved to Hebden Bridge with Caroline in 2006, one of the first things I did was to yomp up the nearest hills so I could look out over the valley and get a sense of where I was; first High Brown Knoll, then Stoodley Pike. It has always been the way I get to know a new place, but is particularly necessary in the claustrophobic narrows of the Upper Calder Valley. What I found remarkable on both Midgley Moor and Erringden Moor, though, was the failure of the map to convey the paths across these moors. For anyone who holds Ordnance Survey maps in as high esteem as I do, it is a shock when they let you down. The map shows public footpaths where there are just swathes of heather and bog, and then you stumble across a fine path (like the one along Sheep Stones Edge) that is not shown at all. Although there is little the OS can do about the vagaries of the historical network of Public Rights of Way, I found the usually reliable black dashed lines letting me down as well. The consequence was that in many places you are forced to navigate by base geographical features (contours, watercourses, crags, etc) alone. While this may be a good navigational exercise, I felt there was an opportunity to map these moors more accurately.

So, finally, after years of amateur map-making, I felt as if I’d hit upon a project to which I could dedicate my passion for exploring the minutiae of the world outside my door. Though the original maps of Wadsworth Moor inspired by these first outings were consigned to the dustbin, but they set in motion the work that became my first book, The West Yorkshire Moors. I squeezed in time between jobs surveying Public Rights of Way and National Trails, though there were many occasions when it felt like a busman’s holiday. I was lucky, though, that my work included walking each of the 2500km of paths in both Kirklees and Calderdale during this period, and slowly a fuller picture of West Yorkshire’s moorland landscape emerged. Aware that obvious comparisons would be made with Wainwright’s style, I never looked at his Lakeland books while producing my maps. When I finally did I was surprised at some similarities of phrase and style, but almost more so by how much more I was cramming on every page (some suggesting a free magnifying glass should be provided with every copy of the book).

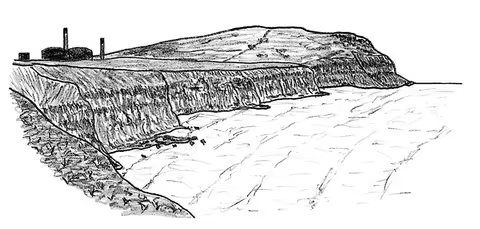

When The West Yorkshire Moors was published in September 2013, I knew I had produced something of genuine quality, but I was still very surprised by the response to it. The publisher did an initial run of just 50 books, which I sold in a weekend, then a couple of hundred more, which went in days. For a while, there was palpable demand around Hebden Bridge and people were telling me how much they valued the book, so much so that they didn’t want to take it out on a walk and sully it. What surprised me most was people telling me how much they liked the sketches – something I had added to the book out of necessity rather than passion. I saw them as rather child-like representations that complimented the maps and text, but I never thought that I could actually draw until people started referring to me as an artist.

The publisher eventually realised how popular The West Yorkshire Moors was and it has sold steadily since, but I had already begun work on the follow-ups. The Wales Coast Path had been under consideration since surveying the whole route with Katharine Evans for the Countryside Council of Wales, but now I finished it with renewed vigour. Published in March 2014, it is a very different style of book, its hand-drawn maps simple and full of glossy colour photos, but it was the first book for this long distance route and remains popular.

I also started work on The West Yorkshire Woods at the same time, vowing that it wouldn’t take me 7 years to produce another book of similar detail. In the end, it took me just 2½ years as I worked with new vigour and focus, inspired by every kind word said about my previous work. I donned my boots and returned to a familiar area but an entirely different landscape, and was surprised with what I found, both in the woods at the end of our road and those amid the mines, mills and quarries around Halifax. The process is still as laborious but it is becoming better-honed, and now it already seems to be just what I do.

I have now published subsequent books on The West Yorkshire Woods: Parts I & II (I quickly realised there were too many woods in the county to cover in a single volume, with Part III on the Colne, Holme and Lower Calder Valley now underway); The South Yorkshire Moors (quite possibly the second part in a Yorkshire moors trilogy, with The North Yorkshire Moors completing the set); The Yorkshire Coast; and the first two of a series of four books on the England Coast Path. But there is still so much more to cover, and who knows where my mapping adventures may lead next.